Increasingly, museums and fine art institutions are contracting out for framing of art works and heritage items. The aim of this article is to help define the information needed from both the institution’s and framer’s perspectives, in the hopes that improved and stream-lined communication can lead to both a better framing package and potential savings in cost and time.

The priorities of an institution and those of a contract framer may not always coincide. Contracting for framing can be a time consuming process for both parties. Framers may spend many hours preparing a quote, taking into consideration both conservation issues and frame durability and longevity. Museums often require multiple quotes which are reviewed by different departments, each with their own parameters and budgets. There can be frequent back-and-forth questions from both sides, and framers will often differ in their methods and approach, resulting in quotes that can vary widely. These multiple layers of information, or lack thereof, can lead to mixed results. In some situations works can end up needing to be re-framed due to structural failure of the frame or, in more extreme cases, damage to the art work itself. One framer estimates that around 70% of works entering their workshop require conservation treatments prior to framing due to issues arising from past framing decisions.

Photo courtesy of Bark Frameworks.

Full and open communication between customer and framer can reduce this risk. Critical information, such as high quality images with a ruler included for scale, and the type and current condition of the work, plays a large role in the success of the framing process. The material a work is made from, and its age and origin, may also dictate framing decisions. These could include, among other things, the moulding style and whether or not the interior of the frame should be sealed. Display location and lighting conditions may also influence glazing choice and package design. Although all of these details may seem extensive and excessive, sharing complete information from the beginning could save time in the long run. The outline below is designed to help get the conversation started, with the understanding that there may be other critical details specific to projects that are not included here.

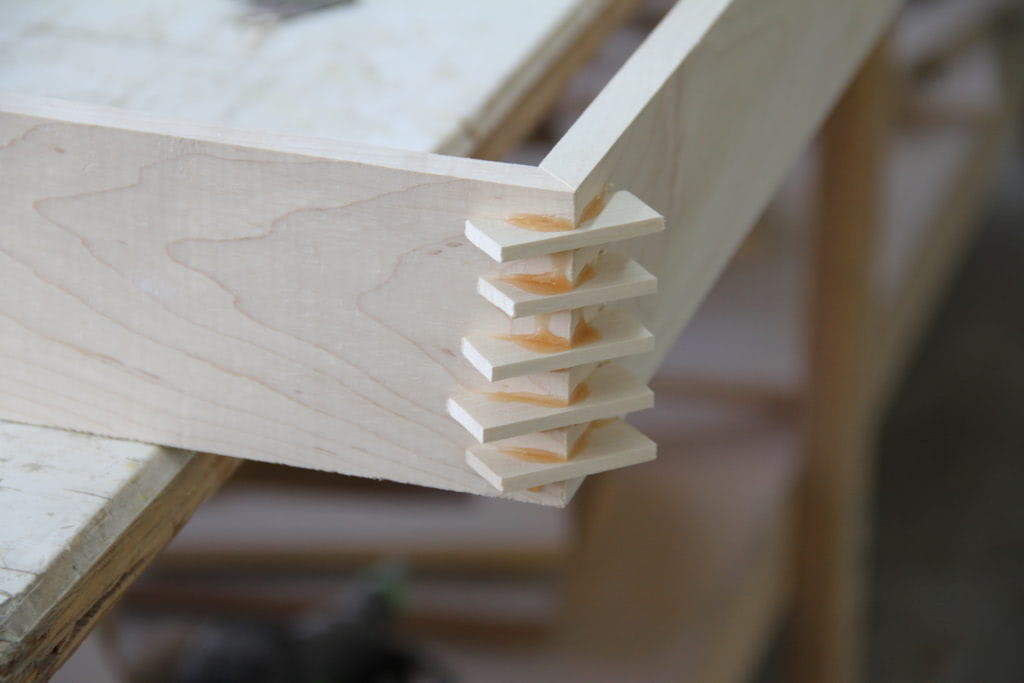

Taking all of the parameters listed above into consideration, basing the decision on who should frame the art work solely on cost can be a mistake. One framer may charge 20% less than another, but the quality of the work and materials used may be far inferior. Two aspects that can greatly influence cost and structural stability are the type of moulding join (pin joins are cheaper, splined joins are stronger) and the type of glazing (thinner glazing might reduce the price, but may be structurally less stable).

Photo courtesy of Bark Frameworks.

Scheduling can also play a large role in the overall cost. The earlier a framer is aware of a project, the easier it will be for them not only to source materials at the lowest price possible, but also plan ahead and budget work hours for the multiple employees needed. This can include designers, fabricators, fitters, and others involved in the project.

Continued communication with a framer after receiving a higher quote is recommended. Most framers want to know why their quote was rejected, and are often open and willing to work within budget constraints once they are aware of them, in order to better serve their clients. By continuing to communicate with the framer one may end up with a better product at a lesser cost.

As more and more institutions are contracting for framing, an increased understanding of how both museums and framers work can help facilitate the experience and offer the best quality framing package possible within budget. Looking at numbers alone can be misleading. Framing materials and construction choices may be based on quality and not necessarily reflect the lowest cost possible. A client shopping around should keep this in mind, especially if the decision to go with one framer over another is based on price alone. It is highly recommended to ask specific questions from each framer that is providing a quote to understand the reasons behind their choices.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to everyone who offered their thoughts and advice for the preparation of this article, including:

Jared Bark, Bark Frameworks

Jane Berman, OTA House

Friedrich Conzen, Conzen

Elise Effmann Clifford, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

Reinhold Gras, Sterling Art Services

Victoria Hanley, National Museums Scotland

Brian Isobe, F M Artist’s Service

Matthew Jones, John Jones

Patricia O’Regan, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

Hannah Payne, John Jones

Natasa Morovic, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

Janice Schopfer, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Bryan Whitney, OTA House

Share this Article:

This article is intended for educational purposes only and does not replace independent professional judgment. Statements of fact and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) individually and, unless expressly stated to the contrary, are not the opinion or position of Tru Vue or its employees. Tru Vue does not endorse or approve, and assumes no responsibility for, the content, accuracy or completeness of the information presented.