By Victoria Hanley, Paper Conservator, National Museums Scotland

Introduction

The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial is a temporary exhibition on at the National Museum of Scotland (NMS), Edinburgh until 3 September 2017. It represents the story of one tomb, built around 1290BC and reused for over 1000 years. On display are a range of stunning artefacts, textiles and papyri mostly found either in, or nearby the tomb. The exhibition is a forerunner to a new permanent ancient Egyptian gallery at NMS, due to open in early 2019. This article will focus on describing the work undertaken on the papyri, from the conservation of these beautiful and ancient objects, to bespoke framing and glazing choices, including the first use of acrylic for the framing of ancient Egyptian papyri.

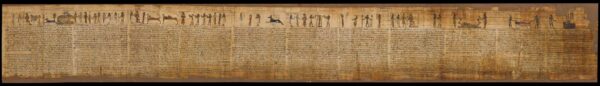

Three significant papyri are on display in The Tomb. They entered NMS’s collection in the mid-19th century, and as such were relatively un-conserved and poorly framed. Two of the papyri belonged to the last inhabitants of the tomb that are featured in the exhibition; a Roman-era high official named Montsuef, and his wife, Tanuat. Their unique bilingual funerary papyri, dated precisely to 9BC by the inscriptions, are some of the highlighted objects in the exhibition, along with a third papyrus; a Book of the Dead of the Vizier Useramun, consisting of eleven fragments, dating back to the 18th Dynasty (approximately 3,500 years ago).

Conservation of the Funerary Papyri

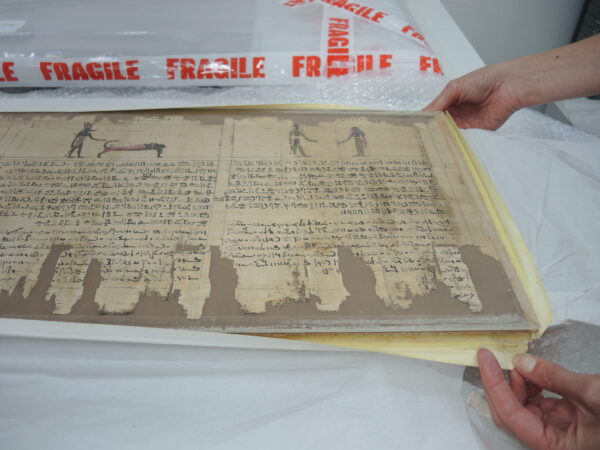

At the time of acquisition, the objects were unrolled and adhered to a poor-quality brown card with an unidentified adhesive (see Fig. 1 & 2).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Initial assessments of the papyri in 2016 determined that although the backing card was in poor condition, it would be too risky to attempt its removal and so the conservation work focused on stabilisation of the media and support, scientific analysis of the pigments and high-quality framing. A great challenge to the paper conservators was undoubtedly size, with the largest papyrus measuring 9 feet (2760mm) in length.

Fig. 3

Backing reduction and consolidation

The cockled brown card backings were reduced with a sharp scalpel following the contours of the object, leaving a small border around the papyrus. There were some localised tears and areas of weakness on the larger papyri and these were supported with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste.

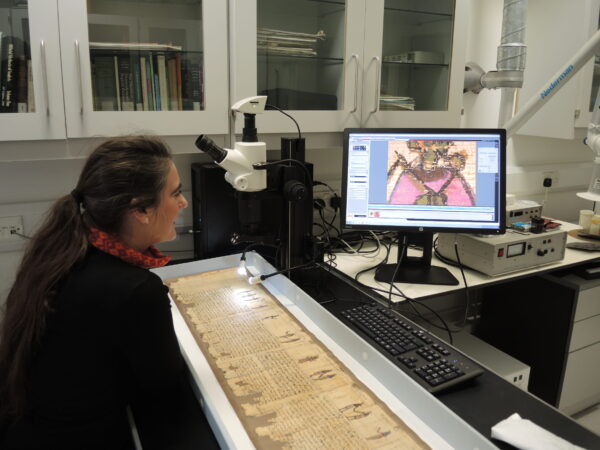

Consolidation of loose, flaking or friable areas of the papyrus support and pigments was carried out under magnification with a 4% solution of Methyl Cellulose applied with a fine brush (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Reposition of Fragments

Tanuat’s papyrus had some fragments that were incorrectly positioned on the brown card. In discussion with the curator, the paper conservators removed the fragments and re-positioned them in their rightful place, thereby allowing the papyrus to be read coherently for the first time since acquisition. The treatment proved challenging due to the fragility of the support and the complex nature of realigning the fragments (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Pigment Analysis

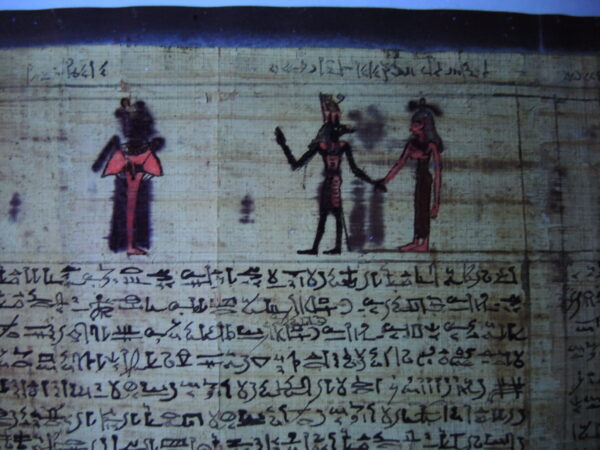

A vivid pink pigment is present on Tanuat’s papyrus; although common on Roman-era burial objects, its use on a funerary papyrus is deemed quite rare. Detailed scientific analysis of the pigment was firstly conducted using ultra-violet light which showed an orange fluorescence (see Fig. 6), a characteristic of the use of matter dyestuff.

Fig. 6

Stereo microscopy and Electron microscopy analysis helped to capture dramatic images that highlighted the pink pigment’s composition; it is based on a white alunite or related pigment mixed with the pink dye (see Fig. 7). Further investigation using liquid chromatography helped to determine that the pink dye is probably rubia peregraina L., also called wild madder, a dye known to be available and in use at that time in Egypt. Further analysis will be conducted post-exhibition to firm up these exciting finds and confirm that the bright pink pigment is indeed madder.

Fig. 7

Conservation Mounting

Japanese tissue hinges were adhered to the back of the papyri’s brown card at regularly spaced intervals and positioned in place to the underside of conservation grade mount board. This created a reversible mounting system for any potential re-positioning requirements in the future (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8

New curatorial research led to the understanding that the placement order of the fragments of the Book of the Dead papyrus was incorrect. Curator and paper conservators collaborated in altering their order and dividing them into three frames to devise a legible and aesthetically pleasing method of display (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 9

Framing & Glazing

A bespoke method of framing was sourced to fully protect these delicate objects and offer safe and visually attractive display for exhibition. John Jones Framers London offered a bespoke framing service, tailoring each frame to suit the needs of the individual object. The priority was to design a ‘front-loading’ frame to avoid placing the objects face down and putting the delicate inscribed surface at risk. Rather than sandwich the papyri between pieces of glass, a solution favoured by some museums, spacers were fitted to separate the papyri from the glazing. Both laminate glass and acrylic glazing was considered but Tru Vue 6mm, Optium Museum Acrylic glazing was favoured for its UV protection, non-reflective, anti-scratch, anti-static properties. A sheet of 6mm was also large enough to accommodate the long papyri, was thick enough not to flex, and its lighter weight made it an attractive option.

Regular dialogue was maintained between John Jones and NMS and once assembled, the frames were shipped to Edinburgh as ready-made packages. The frames comprised a tulip wood sub-frame with an impermeable rigid support adhered to the top acting as a barrier layer. Fixings were attached to the back of the sub-frame prior to fitting the objects. The mounted papyri were then placed directly onto the rigid support, face-up and a plain oak moulding, fitted with Optium Museum Acrylic and spacers fitted over the top. The moulding screwed into the sides of the sub-frame, thereby preventing any need to turn the object (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10

Conclusion

This project offered positive conservation challenges and opportunities for successful collaboration with internal and external stakeholders. The papyri look stunning in their new frames and will remain safe and secure for future display and storage for years to come (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11

Acknowledgements

- National Museums Scotland are extremely grateful to Tru Vue Inc. for the generous donation of Optium Museum Acrylic glazing for this exhibition.

- Thank you to David Palmer of Wessex Pictures, who offered a complimentary cutting and delivery service of the Optium Museum Acrylic glazing.

- Thanks to Frankie Wray and Matt Gray at John Jones, London.

About The Author(s)

Victoria Hanley

Paper Conservator, National Museums Scotland

Victoria Hanley has worked at National Museums Scotland as a Paper Conservator for over 10 years. She has an MA in the Conservation of Fine Art (Works of Art on Paper) from the University of Northumbria at Newcastle. Her interests encompass all aspects of the museum and fine art world. Her work entails complex paper conservation treatments on a variety of objects, managing a diverse work programme to deliver exhibitions and galleries across the museum, whilst continually developing internal and external communication to improve and promote conservation and the organisation.