I saw the rings around Saturn

Shocked I stand on the edge of silence

A big breath before the jump

Hopefully it will be Alright

The artist Gillian Germain explains her inspirations, working process, and the challenges presented by these inherently vulnerable art objects. Their preventive conservation requirements, safe handling and installation are considered, alongside a simple functional display aesthetic in tune with Gill’s artistic intentions.

I am a paper cutter. I live in an isolated house high on a hillside in the Northern Pennines of England. I sit at my table under a glass ceiling looking out at the changing face of the fell. The skies are huge and the heather clad hills are dressed by the mood of the day. The sounds are of lapwing and curlew in the summer months, of sheep always, of wind and of weather. Night time is moon shadow bright, pitch black dark, or veils of stars thrown over the deep well of the sky.

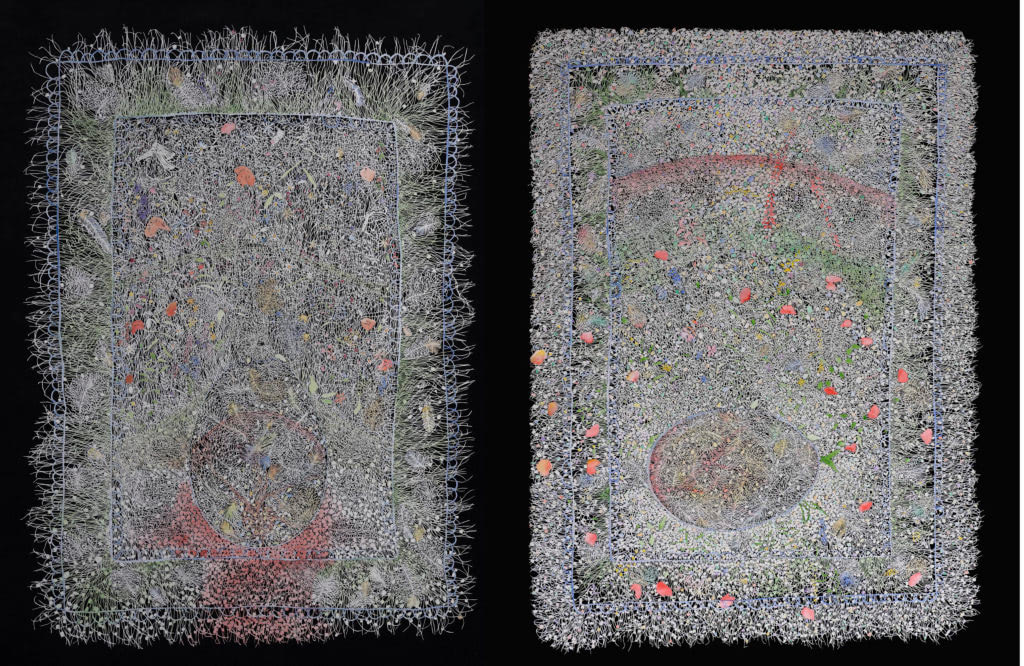

For the past few years I have been cutting paper, drawing with a knife, slowly telling the story of this place and my place in it; my feelings for it, my fears for it, my thoughts about and my love for it. This place is just a drop in the ocean of the world, but it is a living breathing essential part of the world’s well-being.

I work freehand with a knife. Layers of paper are laid over the work to protect it from the movement of my hands, and through a small window of about an inch or two I slowly cut away and watch the spaces fill with the intricate lines of nature that grow and connect. Over time, the cutting has become more and more intense. All the while though, I have a strong feeling of whatever it is that I want to express. A rough sketch places it on the paper, I add washes of watercolour, and from the first cut I follow the impossible lines and connections and find the rhythm of the cutting.

The process is slow and it can take up to a year to complete, so there are not many. Until the very end of the process, I don’t really see a piece as a whole, and from that moment of completion it takes time for me to get to know it. They are all extremely fragile, and handling them makes me feel nervous. For the most part the cuts are stored flat, in a box, in a drawer, and it’s been a long process to find a way to display them safely, in a way which would work for me.

Visually, they are somehow on the edge of invisibility, and hard to look at. I wanted them to float in air, with the light able somehow more safely to pass over and through them. I wanted the drawings to be revealed by their shadow projections, for as they change their appearance, different aspects can appear and new stories emerge. I felt they could become three dimensional when hanging in the air, quiet and beautiful.

The idea that they could be hung freely floating and freely moving rather than sandwiched between two sheets of glass, came to mind. I set to work with my friend, the artist and maker Peter Evans, to design a clean and simple frame, sketching my idea of being able to lower the cut into a box in the same way a bee keeper lifts and drops honey combs into a hive. Pete cleverly came up with the solution of sliding the glass into grooves cut front and back in an oak frame, the lid locking in neatly on top of the papercuts I’d laced with cotton threads from a narrow rod.

It’s a beautifully simple box, but the problem with using glass immediately became evident; it makes the frames heavier, and it’s tricky to slide into the grooves safely without risk of shattering – a potential catastrophe for such fragile pieces. We needed a lightweight minimal aesthetic without the static charge standard acrylics have, which would have risked pulling the delicate artwork to the glazing surface.

The Optium Museum Acrylic solves these problems. The paper cuts float in their display boxes beautifully. I can see their shadows drawn on the surface of the wall and know that they are protected from UV, so their delicate colours are less likely to fade. As the light moves across these works, they play with your eyes and change as time moves across the room. One can look slowly at the changes playing with the intensity of the shadow drawings, see them from both sides, watch a work breathe inside its box and follow the moving rhythm of the lines. It is like there is nothing there but air, and yet they are safe.

Share this Article:

This article is intended for educational purposes only and does not replace independent professional judgment. Statements of fact and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) individually and, unless expressly stated to the contrary, are not the opinion or position of Tru Vue or its employees. Tru Vue does not endorse or approve, and assumes no responsibility for, the content, accuracy or completeness of the information presented.